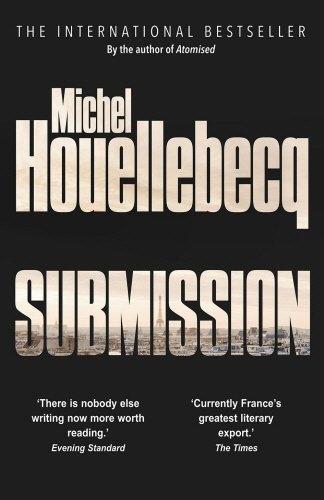

Michel Houellebecq

Submission: A Novel

Trans. Lorin Stein

London: Heinemann, 2015

Michel Houellebecq is one of the finest novelists living today. His most recent novel, Submission, is now out in English. It confirms my long-held suspicion that Houellebecq is a man of the Right, whether or not he admits it to us, or even to himself.

Michel Houellebecq is one of the finest novelists living today. His most recent novel, Submission, is now out in English. It confirms my long-held suspicion that Houellebecq is a man of the Right, whether or not he admits it to us, or even to himself.

Houellebecq has long been one of the most savage critics of liberal decadence and cant. But Submission reveals that he is also a student of far Right literature, showing a broad familiarity with demographics, eugenics, Traditionalism, European nationalism, distributism, biological race and sex differences, Identitarianism (which he calls “Indigenous Europeanism” in the book), and the critics of Islam.

[3]Submission (a translation of “Islam”) tells of a Muslim takeover in France in 2022. The National Front and a fictional Muslim Brotherhood party make it into the runoff in the French national election. On election day, they are neck and neck. Ballot boxes are stolen, invalidating the entire vote. Another vote is scheduled for the following Sunday, but in the meantime, the conservative and Socialist parties join the Muslims in a “Republican Front” to keep Marine Le Pen out of power. Once installed, the Muslim Brotherhood institutes sweeping educational, economic, and foreign policy reforms designed to make Muslim hegemony permanent. Belgium is the next to fall, but all of Europe is doomed due to the political and economic integration of the Muslim world into the European Union.

Houellebecq’s scenario is highly unlikely, at least in the time-frame he specifies. But lack of realism does not prevent science fiction from being an instructive mirror for modern society, and the same is true of Submission, which is less about Islam than about the weaknesses of modern France — and of its would-be defenders on the radical Right — that make them susceptible to a Muslim takeover. Although millions will read this book, I believe that its chosen audience are the intellectuals and activists of the nationalist Right. Houellebecq wants us to succeed. He wants us to save Western civilization. But he does not think we are quite up to the task, so he offers some sage advice.

The End of Democracy

[4]The first lesson of Submission concerns the political process. The Left and the center-Right are both committed to dissolving France into Europe and then into global “humanity.” They are more opposed to French nationalism than to Islam, even though Islam represents a repudiation of their liberal and Republican values. They hate the National Front, and the nation it represents, more than they love themselves and their values. Therefore, out of suicidal spite, they would be willing to put France under a Muslim regime.

But wouldn’t the Left and center-Right wake up eventually and resist as the Muslims began to implement their program? Houellebecq thinks not. The Left would be unable to protest because Islam is a sacred non-white, non-European “other,” and the Right would be unable to protest because they are bourgeois cowards who follow the lead of the Left. The fact that both groups fear Muslim violence does not help either. (None of them fear Right-wing violence, however.)

But if liberal democracy is a sordid, pusillanimous sham which is willing to deliver the nation and itself to destruction, then why is the National Front seemingly committed to democratic legitimacy? Putting a Muslim party in power is not politics as usual, in which power circulates between different branches of the same elite. It is the emergence of a new elite with a radical revolutionary agenda. Islam aims at irreversible change, hence it punishes apostasy with death. It is not just a flavor of liberal democracy that can be installed by a minor tantrum of the voters and then reversed on whim at the next election.

If this is how democracy ends, then why is the Right unwilling to end democracy in order to save the nation? Houellebecq sets up a scenario in which the only salvation of France would be a Right-wing revolution or military coup, followed by both massive ethnic cleansing and an épuration of the ruling classes, including “the soixante-huitards, those progressive mummified corpses — extinct in the wider world — who managed to hang on in the citadels of the media, still cursing the evils of the times and the toxic atmosphere of the country” (p. 126).

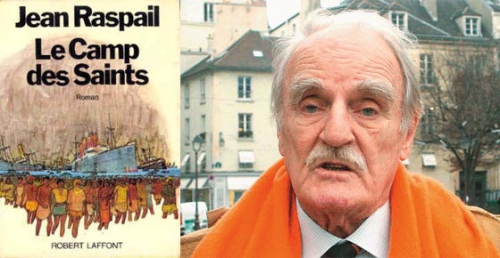

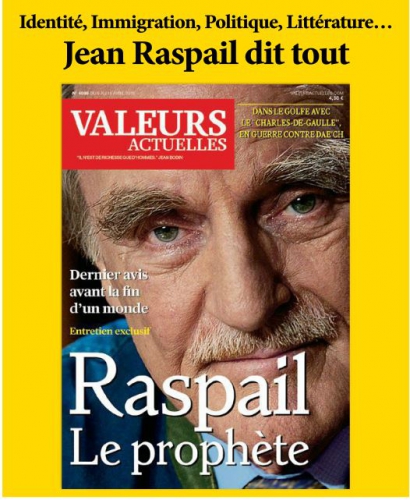

It goes without saying that the Muslims are willing to kill and die to get their way, but the Right, apparently, is not. In Submission, as in Jean Raspail’s The Camp of the Saints, even the most martial and patriotic French are so rotted with humanitarian cant and cowardice that they allow their country to be destroyed rather than use force to preserve it. I refuse to believe that the French Right is quite that decadent and that Marine Le Pen or her successor would allow a great nation with a venerable tradition of revolutions, coups, and dictatorships to perish out of cuckservative good sportsmanship.

Why are young Rightists not entering the French army and police forces? Why are they not opening private security firms? If none of this had occurred to the leaders of the National Front and the Identitarians, it has now. If so, perhaps Houellebecq will some day be remembered as the Rousseau of the next (and final) French Revolution.

Post-Democratic Legitimacy

The next lesson of Submission concerns how to legitimate a post-democratic society. And make no mistake: even though the form of elections might be maintained, the Muslim Brotherhood would never allow itself to be voted out of power. Specifically, how would the Muslim Brotherhood neutralize its most committed enemies on the far Right, the traditionalist Catholics, the Identitarians, and the National Front? Simple: by instituting reforms that they wanted all along.

The Muslim Brotherhood is in no hurry to impose sharia law. The French may not fight for nation and freedom, but they will fight for alcohol and cigarettes. Christians and Jews will not be persecuted. The Muslims realize that the future belongs to the population that has more children and passes on their values to them. The native French population is shrinking. In a few generations, they will be virtually extinct, and those who remain will be powerless to resist sharia law. So all the Muslim Brotherhood has to do is wait.

In the meantime, they are content to reform the educational system, one of the bastions of the Left. Muslims are given the option of a completely Muslim education. Co-education is abolished. Female teachers are pensioned off. Schooling is mandatory until only the age of 12. Vocational training and apprenticeships are encouraged. Higher education is privatized. The public universities are Islamized with huge influxes of petrodollars. Non-Muslim male faculty and all female faculty are given early retirements with full pensions.

In the economic realm, the Muslim Brotherhood eliminates unemployment by giving incentives to women to leave the workplace and return to family life. Small, family-owned businesses are encouraged through adopting Catholic distributist policies. Welfare spending is slashed dramatically, forcing people to work in good times and to depend on their families and religious communities in hard times.

In the social realm, the patriarchal family is reestablished as the norm. Women are encouraged to choose families over careers. Sexual modesty in dress, behavior, advertising, and popular culture is rapidly adopted. Oh, and Muslim men are allowed up to four wives.

In the social realm, the patriarchal family is reestablished as the norm. Women are encouraged to choose families over careers. Sexual modesty in dress, behavior, advertising, and popular culture is rapidly adopted. Oh, and Muslim men are allowed up to four wives.

Crime, which is mostly Muslim crime to begin with, plummets, perhaps because they feel that France is now their country and they no longer wish to trash it.

Now, dear reader, ask yourself: wouldn’t you wallow in Schadenfreude to see the Leftist academics, feminists, and welfare scroungers get theirs? Wouldn’t you rejoice at such pro-family reforms? And that’s the problem.

In the long run, under Muslim rule, France will disappear, and the only force that could prevent it is the far Right. But the far Right, like every other group, has a majority of short-sighted people and a minority of far-sighted ones. The far-sighted can only mobilize the short-sighted based on their present discontents. Drain the sources of discontent, and the far-Right constituency will grow complacent. And without followers, the leadership will be powerless.

The far Right is also a coalition of people with varying complaints. Only a minority are true racial nationalists who realize that to be French, one must be white. A black can be a French citizen, speak French, eat French food, and be a Roman Catholic. Thus citizenship, language, culture, and religion are not essential to being French. But whiteness is.

Many Rightists do not see this, however. They are broad-brush anti-modernists and reactionaries; traditionalists with a large or small “T”; anti-feminists, masculinists, and “Men Going their Own Way”; or devotees of dead or dying religions and deposed dynasties. Such vague and anachronistic yearnings will never be fully satisfied anyway. There will never be another king Clovis, who will re-Christianize France. So many of these people would be quite happy to live under a moderate Muslim regime which is traditional, patriarchal, hierarchical, and appeals to transcendent values.

After all, we have ample evidence of impotent Rightists being willing to accept vague approximations to their values and submerge their reservations, as long as the approximation is better organized and more active than the Right, which isn’t hard. Thus in America, I have seen actual National Socialists converted into fervent enthusiasts for Ron Paul, Vladimir Putin, Alexander Dugin, Catholicism, Orthodox Christianity, Traditionalism — anything, really, as long as it appears to be a sizable and well-organized opposition to the existing establishment. You know very well what such weak reeds would do when confronted with an actual Muslim regime. After all, opposing Islam would be “anti-traditional.”

There are many lessons for White Nationalists here. First, never let a Muslim regime come to power. Instead, prevent that — and gain power for ourselves — by any means necessary. Second, we must work relentlessly to focus our people on the paramount importance of race and not to fall for approximations and half-measures. Third, once we have power, we should not be in any hurry. All we need to do is hold onto power — which means postponing more radical reforms for a later date — and be content to set social processes in motion that will in the long-term lead to the sort of society we want. Focus on education and the family. Be kind to workers and small businessmen. Encourage the white population to grow and the non-white population to emigrate [6]. Deliver prosperity, security, and peace to our constituents. And then wait.

The Jewish Question

Now you may be wondering where the Jews fit into this. As Guillaume Durocher points out [7], Houellebecq hints at the importance of Jewish power, but in his narrative, Jews have no agency whatsoever. They simply slouch off to Jerusalem when the Muslim Brotherhood comes to power. In France today, however, Jews are a formidable political force, and Muslims are far weaker than their numbers would predict. Indeed, Jews have played a dominant role in encouraging Muslim immigration and empowerment, and in stigmatizing French resistance. Perhaps Houellebecq thinks that Islam will turn out to be another golem that turns on its Jewish masters. Maybe he wishes to focus specifically on the susceptibility of the French to Muslim domination. Or perhaps he thinks that Jews can be persuaded to change sides, which strikes me as extremely naive [8].

Surrender and Collaboration

The next lesson of Submission concerns the psychology of surrender and collaboration. The main character of Submission is François, a 44-year-old professor of 19-century French literature in Paris. (He is a specialist on Joris-Karl Huysmans.) François is an only child (of course), the offspring of two selfish baby-boomers (divorced, of course) of the type that Houellebecq so masterfully skewers in his other books. He has had no contact with his parents in years, and he learns of their deaths only after the fact.

François is obsessed with sex (of course, since this is a Houellebecq novel). He has never married (of course). Instead, he has a series of transient relationships with young female students, who always seem to be the ones who break it off (of course), perhaps to show how strong they are.

François’ intellectual life is as empty as his personal one. The author of a brilliant dissertation, he has published one book, been promoted to full Professor, and now whiles away his time with petty academic politics.

Although a student of French literature, François knows very little about France. He seems utterly cut off from any sense of national identity. Left to his own devices, he eats nothing but Oriental, Middle Eastern, and Indian food, generally of the frozen or take-out varieties. (Let that sink in for a minute. How could any self-respecting Frenchman eat shwarma?) He lives in Paris’ Chinatown. He envies his Jewish soon-to-be-ex-girlfriend’s tribal identity, ruefully remarking that, “There is no Israel for me.” (Yes, but who made it so?)

François is also a chain-smoker and a massive alcoholic, although these hardly distinguish him from other European men today.

Desperately unhappy, François tries to follow Huysmans’ path into the Catholic Church, hoping it will provide a ready-made, all-encompassing meaning for his life. But it does not take. At one shrine, he has a quasi-mystical experience, but he interprets it as hypoglycemia. On another attempt, at a monastery, he flees after three days from the cold, discipline, deprivation, and forced sociability back to his solitude, cynicism, and cigarettes. Christianity demands sincere commitment, which François cannot give, and it offers very few creature comforts, which he cannot give up.

Naturally, François’ utter self-absorption goes along with political passivity. He barely took notice of politics until his country was torn away from him, and then he did absolutely nothing to fight it. When he hears of the possibility of a civil war, he wonders only if the deluge can be postponed till after his death. The very idea of fighting or dying for France would never have crossed his mind. But men who care about nothing higher than comfort and security, no matter how clever and civilized they may be, are no match for men who are willing to kill or die for higher values, no matter how stupid and primitive they may be.

After the Muslim takeover, François is forced into early retirement at full pension. But then he is slowly reeled back in by Robert Rediger, the Belgian-born convert to Islam who is put in charge of the educational system. First, at Rediger’s instigation, François is invited to edit an edition of Huysmans for the prestigious French publisher Pléiade. Then Rediger invites him to a reception, where they meet. At the reception, Redinger invites François to his home for a conversation, where Rediger reveals that he is recruiting distinguished scholars from the old system for the new Islamic University of Paris-Sorbonne. All François need do is convert to Islam, which he does.

Why does François convert to Islam rather than Catholicism? One reason is that Christianity is a feminine religion that inspires contempt, and Islam is a masculine religion that inspires admiration. But the main reason seems to be the fringe benefits. Christianity offered him swooning and self-denial. Islam offered him self-assertion and material advancement: a job at the Sorbonne, a huge salary, a house in a fashionable part of Paris, and most importantly, a cure for his sexual frustration and loneliness. Rediger offers him three wives, for starters: young, nubile, submissive Muslim girls to share his bed and bear his children.

Why does Houellebecq center his narrative on an academic? Because this novel is a thought experiment. Academia is the stronghold of the Left, which is still the strongest metapolitical force in our society, and if Islam can break its resistance, it can break anything else. Houellebecq realizes that academic males are pretty much all sexually frustrated wimps, dorks, and slobs: beta males oppressed by strong womyn in both their professional and personal lives. He believes they would welcome a regime that forces modesty in dress and advertisements, so they are not constantly tormented with sexual thoughts; a regime that restores male dominance in the workplace and bedroom; a regime that suppresses feminism and encourages female submission. Being married to four modern Western women sounds like hell on earth, but Islam might make polygamy quite workable. Houellebecq supports something I have long suspected: fundamentalist religions appeal to beta males as a way of controlling women. (“Jesus wants you to make me a sandwich, dear.”)

Polygamy, of course, is not the white way. But Rightists need to take note. Feminism is probably the greatest source of misery for men, women, and especially children today. White Nationalism is all about restoring the biological integrity of our race. That means not just creating homogeneously white living spaces for the reproduction and rearing of our kind, but also restoring traditional (and biological) sex roles: men as protectors and providers, women as mothers and nurturers. If we can promise to restore stable and loving families and homogeneous, high-trust communities, we can drain the swamps in which Leftists breed. After all, how many Leftists do you know who are lonely, dysfunctional, socially alienated products of broken families and communities?

Beware the Traditionalists

The most interesting character in Submission is Robert Rediger, the Education then Foreign Minister of the new regime. He is a master of persuasion who knows that academics suffer above all from sexual frustration and unrequited vanity. He is a master of religious apologetic, meaning that he is an exceedingly clever liar. He claims that the Koran is a great poem of praise for creation, when it is closer to gangsta rap both as poetry and edification. He claims that polygamy is eugenic, which it might be if Muslims didn’t marry blacks and their own first cousins.

Rediger is a large, masculine man, which makes him an unusual academic. But this comes as no surprise when we learn his history. As a young man in Belgium, Rediger was an ardent Right-wing nationalist. But he was never a racist or fascist, mind you. Just a broad-brush reactionary anti-modernist who wrote a dissertation on Nietzsche and René Guénon, anti-modernist thinkers with radically incompatible premises. This does not, however, prevent Rediger from shifting from one perspective to another whenever it suits him. Nietzsche destroyed Christianity for Rediger, and Guénon offered him a way into Islam, a religion he sees as more compatible with masculine and vitalist impulses.

The lesson here is obvious: if racial integrity is not paramount, then Traditionalism is a vector of Islamization. A demythologization of Traditionalism has long been on my agenda, and Houellebecq has convinced me to step up the timetable. Such an argument has two prongs. First, as I argued in my review of Jan Assmann’s Moses the Egyptian [11], the Traditionalist thesis of the transcendent unity of religions is actually heretical according to the Abrahamic faiths, Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, which reject all other religions as false. Second, the Traditionalists are well aware of this problem. Thus their assertion that the Abrahamic faiths are compatible with Traditionalism is merely an attempt to trick their adherents into tolerating esoteric paganism. (Arguing this thesis would require a reading of Ibn Tufayl’s Hayy Ibn Yaqzan [12] and Guénon’s Initiation and Spiritual Realization [13]

and Guénon’s Initiation and Spiritual Realization [13] and Perspectives on Initiation [14]

and Perspectives on Initiation [14] .)

.)

There is no Allah, and Muhammad was not his prophet. Therefore, whatever power Islam possesses is grounded in nature. If there is an overall lesson to Submission, it is that if our civilization falls out of harmony with nature and ceases to pass on its genes and values, it will be replaced by a civilization — no matter how backward and primitive — that is capable of doing so. And European man will disappear in a tide of fast-breeding, savage Sand People.

The Left and center-Right are deferential to Islam because they are decadent and devitalized. They sense its greater vitality, including its potential for violence. These people want to be subjugated, because no tyranny is worse than the fate of the atomized individual floating in the void of liberal, consumerist modernity. Liberal democracy and capitalism supply every human need, except to believe, belong, and obey. If our race is to be saved, then White Nationalists need to bring our societies back into harmony with nature. Whites must be forced to submit to our own nature, or we will end up submitting to aliens. And to do that, White Nationalists need to become an even more formidably vital — and intimidating — force than Islam. Clearly we’ve got work to do.

Related

PHILITT : On trouve dans Les Déracinés une critique explicite de la morale kantienne. Pouvez-nous dire quels sont les enjeux d’une telle critique ?

PHILITT : On trouve dans Les Déracinés une critique explicite de la morale kantienne. Pouvez-nous dire quels sont les enjeux d’une telle critique ? PHILITT : Dans L’Appel au soldat, Barrès raconte la fulgurante ascension du général Boulanger. Voit-il en lui une figure du réenracinement ?

PHILITT : Dans L’Appel au soldat, Barrès raconte la fulgurante ascension du général Boulanger. Voit-il en lui une figure du réenracinement ?

Les Editions Via Romana viennent de publier

Les Editions Via Romana viennent de publier  L'intérêt du livre de Jacques Perret est là, nous narrer l'avant-guerre, « la paix des familles, l'état d'innocence, l'harmonie universelle » ou « la cueillette des prunes », les devoirs de classe, les jeux en plein air, au Jardin du Luxembourg des distractions enfantines, les cabanes et les courses à vélo, agrémentées de pénibles leçons de piano. Dès lors, en lisant le livre, on ne peut pas commémorer la grande guerre sans faire des parallèles avec le repli familial des années 90 qui anticipe ce que sera le choc historique des années 2015-2025. Certes en 1912 pas de grand remplacement ni de théorie du genre obligatoire, de totalitarisme de l'édredon, rien de tout cela dans le portrait d'une famille plutôt traditionnelle d'avant-guerre avec le camembert et le pinard à la sortie de la Messe, ou les enfants montés de force à l'étage quand les grands finissaient d'arroser la soirée au calvados dans le salon : « De fumants éclats montaient jusqu'aux chambres des enfants et nous comprenions alors vaguement dans le demi-sommeil, quelle institution difficile et miraculeuse était la famille où sans être d'accord sur tout on peut s'embrasser à propos de rien ». En réalité, aujourd'hui, les enfants ne dorment plus très tôt, ne montent dans leurs chambres que pour les jeux vidéos tandis que leurs parents pianotent sur leurs portables sans même se parler ou se poser des questions. Mais n'est-ce pas aussi un climat d'avant-guerre, le climat insouciant d'une guerre mondiale qui sera hybride et civile mais dont on veut dénie la probable réalité barbaresque ou nucléaire ? En fait, ce paradis familial que narre Jacques Perret avant la grande catastrophe de 14 existe encore même s'il n'y a plus d'éden républicain capable de fomenter la fierté grandiloquente de l'humble devoir patriotique. Il n'y a plus de nation mais des rapatriements d'exilés ou d'immigrés dans des drapeaux brûlés, déchirés ou remplacés sur les places publiques par les bannières ennemies de républiques islamiques.

L'intérêt du livre de Jacques Perret est là, nous narrer l'avant-guerre, « la paix des familles, l'état d'innocence, l'harmonie universelle » ou « la cueillette des prunes », les devoirs de classe, les jeux en plein air, au Jardin du Luxembourg des distractions enfantines, les cabanes et les courses à vélo, agrémentées de pénibles leçons de piano. Dès lors, en lisant le livre, on ne peut pas commémorer la grande guerre sans faire des parallèles avec le repli familial des années 90 qui anticipe ce que sera le choc historique des années 2015-2025. Certes en 1912 pas de grand remplacement ni de théorie du genre obligatoire, de totalitarisme de l'édredon, rien de tout cela dans le portrait d'une famille plutôt traditionnelle d'avant-guerre avec le camembert et le pinard à la sortie de la Messe, ou les enfants montés de force à l'étage quand les grands finissaient d'arroser la soirée au calvados dans le salon : « De fumants éclats montaient jusqu'aux chambres des enfants et nous comprenions alors vaguement dans le demi-sommeil, quelle institution difficile et miraculeuse était la famille où sans être d'accord sur tout on peut s'embrasser à propos de rien ». En réalité, aujourd'hui, les enfants ne dorment plus très tôt, ne montent dans leurs chambres que pour les jeux vidéos tandis que leurs parents pianotent sur leurs portables sans même se parler ou se poser des questions. Mais n'est-ce pas aussi un climat d'avant-guerre, le climat insouciant d'une guerre mondiale qui sera hybride et civile mais dont on veut dénie la probable réalité barbaresque ou nucléaire ? En fait, ce paradis familial que narre Jacques Perret avant la grande catastrophe de 14 existe encore même s'il n'y a plus d'éden républicain capable de fomenter la fierté grandiloquente de l'humble devoir patriotique. Il n'y a plus de nation mais des rapatriements d'exilés ou d'immigrés dans des drapeaux brûlés, déchirés ou remplacés sur les places publiques par les bannières ennemies de républiques islamiques.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

GF-T : Maurice Bardèche ne fait pas œuvre d’historien. Il puise dans l’histoire des exemples marquants. Quand il rédige L’œuf de Christophe Colomb, il a en tête deux visions d’Europe inachevées ou avortées : l’Europe de la Grande Nation de Napoléon Ier et celle des volontaires européens sur le front de l’Est de 1941 à 1945, la première étant plus prégnante dans son esprit que la seconde.

GF-T : Maurice Bardèche ne fait pas œuvre d’historien. Il puise dans l’histoire des exemples marquants. Quand il rédige L’œuf de Christophe Colomb, il a en tête deux visions d’Europe inachevées ou avortées : l’Europe de la Grande Nation de Napoléon Ier et celle des volontaires européens sur le front de l’Est de 1941 à 1945, la première étant plus prégnante dans son esprit que la seconde.

Chrétien, venu à la cour de l’empereur Barberousse vers 1180, y avait rencontré l’ambassadeur byzantin. Les chansons de geste byzantines étaient proches des nôtres, et Chrétien explique les liens entre cette littérature et nos prédécesseurs.

Chrétien, venu à la cour de l’empereur Barberousse vers 1180, y avait rencontré l’ambassadeur byzantin. Les chansons de geste byzantines étaient proches des nôtres, et Chrétien explique les liens entre cette littérature et nos prédécesseurs.

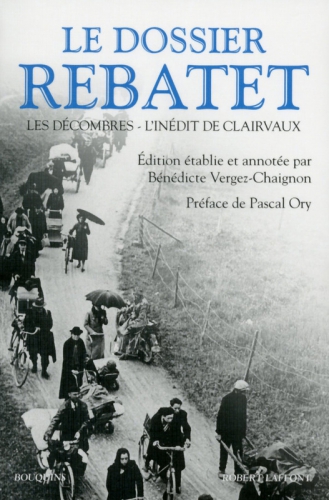

Sorti en 1942, Les Décombres de Lucien Rebatet (deuxième titre majeur après Les deux étendards) viennent d’être réédités chez Robert Laffont. Cinq mille exemplaires épuisés dès le premier jour, l’éditeur a lancé un deuxième tirage à trois mille.

Sorti en 1942, Les Décombres de Lucien Rebatet (deuxième titre majeur après Les deux étendards) viennent d’être réédités chez Robert Laffont. Cinq mille exemplaires épuisés dès le premier jour, l’éditeur a lancé un deuxième tirage à trois mille.

Michel Houellebecq is one of the finest novelists living today. His most recent novel, Submission, is now out in English. It confirms my long-held suspicion that Houellebecq is a man of the Right, whether or not he admits it to us, or even to himself.

Michel Houellebecq is one of the finest novelists living today. His most recent novel, Submission, is now out in English. It confirms my long-held suspicion that Houellebecq is a man of the Right, whether or not he admits it to us, or even to himself. In the social realm, the patriarchal family is reestablished as the norm. Women are encouraged to choose families over careers. Sexual modesty in dress, behavior, advertising, and popular culture is rapidly adopted. Oh, and Muslim men are allowed up to four wives.

In the social realm, the patriarchal family is reestablished as the norm. Women are encouraged to choose families over careers. Sexual modesty in dress, behavior, advertising, and popular culture is rapidly adopted. Oh, and Muslim men are allowed up to four wives.

On a tant écrit sur Drieu. On a un peu l’impression qu’aujourd’hui, le mieux, pour l’évoquer, est encore de le relire. Il y a eu Drieu le petit-bourgeois déclassé, disséqué par François Nourissier — un expert —; il y a eu le souvenir de l’ami, par Berl dans Présence des morts (magnifique évocation d’un adolescent éternel — et c’est compliqué, signifie Berl, lorsqu’on a 50 ans… —) ; il y a eu l’ami encore, par Malraux dans ses entretiens avec Frédéric Grover, ou par Audiberti, dans Dimanche m’attend, un des rares présents aux obsèques de Drieu, en dépit du contexte et en vertu d’une fidélité amicale certaine ; il y a eu Michel Mohrt et l’évocation de Fitzgerald à propos de Drieu, son “cousin américain” (voir leurs rapports avec les femmes, l’argent et la mélancolie).

On a tant écrit sur Drieu. On a un peu l’impression qu’aujourd’hui, le mieux, pour l’évoquer, est encore de le relire. Il y a eu Drieu le petit-bourgeois déclassé, disséqué par François Nourissier — un expert —; il y a eu le souvenir de l’ami, par Berl dans Présence des morts (magnifique évocation d’un adolescent éternel — et c’est compliqué, signifie Berl, lorsqu’on a 50 ans… —) ; il y a eu l’ami encore, par Malraux dans ses entretiens avec Frédéric Grover, ou par Audiberti, dans Dimanche m’attend, un des rares présents aux obsèques de Drieu, en dépit du contexte et en vertu d’une fidélité amicale certaine ; il y a eu Michel Mohrt et l’évocation de Fitzgerald à propos de Drieu, son “cousin américain” (voir leurs rapports avec les femmes, l’argent et la mélancolie).

Le Jeudi:

Le Jeudi:

L’histoire se déroule du 17ème au 21ème siècle, elle est celle du duché de Valduzia, principauté onirique sise aux confins de la Carélie russe. Ses princes héréditaires se sont lancés à la conquête de ces vastes territoires vierges. Pour marquer la prise de possession, ils tracèrent une ligne hypothétique sur des centaines de lieues, la frontière. Les érecteurs de bornes croient marquer leur territoire et conjurer une improbable menace ou affirmer leur propriété en posant des pierres dans une lande de neige sans horizon. Au contraire, les petits hommes de la Taïga pressentent que la présence de ces curieux monolithes annonce leur fin prochaine. Ils comprennent que, désormais, ils devront reculer de forêt en forêt, jusqu’à la soixantième, avant de disparaître. En réponse, ils marquent leur présence au moyen de petits bâtons sculptés et ils lancent un avertissement: un javelot planté dans un arbre. Ces reliques, seules preuves de leur existence seront transmises de génération en génération et elles parviendront jusque dans les mains du narrateur, un professeur d’ethnologie qui tente de reconstituer la légende du petit homme.

L’histoire se déroule du 17ème au 21ème siècle, elle est celle du duché de Valduzia, principauté onirique sise aux confins de la Carélie russe. Ses princes héréditaires se sont lancés à la conquête de ces vastes territoires vierges. Pour marquer la prise de possession, ils tracèrent une ligne hypothétique sur des centaines de lieues, la frontière. Les érecteurs de bornes croient marquer leur territoire et conjurer une improbable menace ou affirmer leur propriété en posant des pierres dans une lande de neige sans horizon. Au contraire, les petits hommes de la Taïga pressentent que la présence de ces curieux monolithes annonce leur fin prochaine. Ils comprennent que, désormais, ils devront reculer de forêt en forêt, jusqu’à la soixantième, avant de disparaître. En réponse, ils marquent leur présence au moyen de petits bâtons sculptés et ils lancent un avertissement: un javelot planté dans un arbre. Ces reliques, seules preuves de leur existence seront transmises de génération en génération et elles parviendront jusque dans les mains du narrateur, un professeur d’ethnologie qui tente de reconstituer la légende du petit homme.

Lichtmesz: Vielen Dank an Herr Ladurner, dass er an diesen wichtigen Roman erinnert hat, der besonders die Leser der ZEIT erfreuen wird, wobei mir scheint, dass er nicht viel nachgedacht hat, als er

Lichtmesz: Vielen Dank an Herr Ladurner, dass er an diesen wichtigen Roman erinnert hat, der besonders die Leser der ZEIT erfreuen wird, wobei mir scheint, dass er nicht viel nachgedacht hat, als er

Hay un reclamo persistente en Drieu: “Voces falsarias y hueras me han acusado de que mi posición surge de un adaptarme a las formas políticas que se proyectan como victoriosas, en este momento de la guerra y que serían las dominantes en el futuro, todo ello es falso”

Hay un reclamo persistente en Drieu: “Voces falsarias y hueras me han acusado de que mi posición surge de un adaptarme a las formas políticas que se proyectan como victoriosas, en este momento de la guerra y que serían las dominantes en el futuro, todo ello es falso” Sobre el particular apunta Drieu: “Me he convencido de que Guénon anuncia, con el lenguaje cifrado propio de la Tradición sagrada de los pueblos, que se aproxima un cambio drástico en la valoración de los hombres y en el sentido de la vida; en ello he visto a las nuevas fuerzas que se alzan contra los dogmas, al parecer inamovibles, de una civilización basada en el dinero, el materialismo y en formas políticas caducas”.

Sobre el particular apunta Drieu: “Me he convencido de que Guénon anuncia, con el lenguaje cifrado propio de la Tradición sagrada de los pueblos, que se aproxima un cambio drástico en la valoración de los hombres y en el sentido de la vida; en ello he visto a las nuevas fuerzas que se alzan contra los dogmas, al parecer inamovibles, de una civilización basada en el dinero, el materialismo y en formas políticas caducas”.

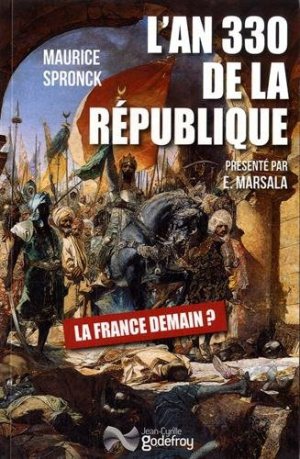

Influencé par Nietzsche et Carlyle, Maurice Spronck publie en 1894 une contre-utopie (ou dystopie). Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella pariaient sur l’avenir ou l’onirisme pour élaborer des systèmes politiques et sociaux parfaits dans lesquels les êtres humains s’épanouiraient harmonieusement au contraire de la dystopie popularisée par les écrivains de science-fiction et d’anticipation (Eugène Zamiatine, écrivain de Nous autres, Aldous Huxley dans Le meilleur des mondes, George Orwell avec 1984, René Barjavel pour Ravage, Ray Bradbury et son Fahrenheit 451). L’an 330 de la République fait de Maurice Spronck un étonnant précurseur.

Influencé par Nietzsche et Carlyle, Maurice Spronck publie en 1894 une contre-utopie (ou dystopie). Thomas More, Francis Bacon, Tommaso Campanella pariaient sur l’avenir ou l’onirisme pour élaborer des systèmes politiques et sociaux parfaits dans lesquels les êtres humains s’épanouiraient harmonieusement au contraire de la dystopie popularisée par les écrivains de science-fiction et d’anticipation (Eugène Zamiatine, écrivain de Nous autres, Aldous Huxley dans Le meilleur des mondes, George Orwell avec 1984, René Barjavel pour Ravage, Ray Bradbury et son Fahrenheit 451). L’an 330 de la République fait de Maurice Spronck un étonnant précurseur.

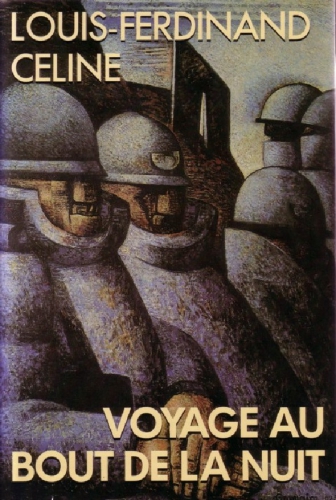

What sticks in memory from both books after lo! these many years, with scarcely a return dip in the meantime, is a miasma of filth, poor sanitation—in the trenches, in the slums, everywhere. (Curiously, Céline’s first book, his doctoral thesis in fact, was a biography of Ignaz Semmelweis[6], the father of obstetric antisepsis.) The obsessive disgust is very similar to the first part of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, which was written about the same time, so one author is unlikely to have influenced the other. Orwell was aware of Céline in the 1930s, since he mentions him in his essay on Henry Miller; but only just barely.

What sticks in memory from both books after lo! these many years, with scarcely a return dip in the meantime, is a miasma of filth, poor sanitation—in the trenches, in the slums, everywhere. (Curiously, Céline’s first book, his doctoral thesis in fact, was a biography of Ignaz Semmelweis[6], the father of obstetric antisepsis.) The obsessive disgust is very similar to the first part of Orwell’s Down and Out in Paris and London, which was written about the same time, so one author is unlikely to have influenced the other. Orwell was aware of Céline in the 1930s, since he mentions him in his essay on Henry Miller; but only just barely.

Di recente è uscita una sua biografia a firma di Antonio Serena, Drieu aristocratico e giacobino, per i tipi della Settimo Sigillo, nota casa editrice di estrema destra. Tuttavia è doveroso strappare questo cattivo maestro alle opposte tifoserie politiche per consegnarlo al posto che merita. Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, nato nel 1893 a Parigi in una famiglia piccolo borghese e nazionalista di antica fede napoleonica, è uno dei figli migliori della generazione perduta. E’ vissuto tra le due guerre: è stato ferito nella prima e si è tolto la vita sul finire della seconda, per l’esattezza il 15 marzo 1945, dopo aver ingerito una dose letale di Fenobarbital. Tutto ciò che lo riguarda, come letterato e come uomo, è accaduto durante quella pace “fatua” andata in scena a Parigi tra le due guerre. Amico di Louis Aragon e André Malraux, dei dadaisti e dei surrealisti, dandy delle serate alla moda, marito fallimentare, amante di donne piacenti e ricche, Drieu in fondo è passato nel secolo breve senza legarsi ad alcuno, fedele alla sua spietata coerenza.

Di recente è uscita una sua biografia a firma di Antonio Serena, Drieu aristocratico e giacobino, per i tipi della Settimo Sigillo, nota casa editrice di estrema destra. Tuttavia è doveroso strappare questo cattivo maestro alle opposte tifoserie politiche per consegnarlo al posto che merita. Pierre Drieu la Rochelle, nato nel 1893 a Parigi in una famiglia piccolo borghese e nazionalista di antica fede napoleonica, è uno dei figli migliori della generazione perduta. E’ vissuto tra le due guerre: è stato ferito nella prima e si è tolto la vita sul finire della seconda, per l’esattezza il 15 marzo 1945, dopo aver ingerito una dose letale di Fenobarbital. Tutto ciò che lo riguarda, come letterato e come uomo, è accaduto durante quella pace “fatua” andata in scena a Parigi tra le due guerre. Amico di Louis Aragon e André Malraux, dei dadaisti e dei surrealisti, dandy delle serate alla moda, marito fallimentare, amante di donne piacenti e ricche, Drieu in fondo è passato nel secolo breve senza legarsi ad alcuno, fedele alla sua spietata coerenza. L’opera di Drieu è una scomoda riflessione sul togliersi la vita. E tutto ciò con il senno di poi sembra rispecchiare la crisi autolesionistica che attraversa l’Occidente. Il bello è che lui credeva nell’immortalità dell’anima, anche se in senso più induista che cristiano. Accanto al suo cadavere fu trovata una copia delle Upanishad. Drieu aveva cercato, affacciandosi alla filosofia, al cristianesimo, infine alle tradizioni dell’estremo oriente, senza trovare una via d’uscita. La sua letteratura dice questa ricerca. Dalle Memorie di Dirk Raspe, in cui racconta Vincent Van Gogh, grande suicida, a Fuoco Fatuo, in cui la morte dello scrittore surrealista Jacques Rigaut, suo sodale, è il presupposto per scrivere di getto i pensieri di un uomo incapace di appartenere alla realtà e di amare perché “non può toccare niente” e soltanto la pistola è finalmente reale, un oggetto solido attraverso cui realizzare finalmente qualcosa di tangibile. Ed eccolo, terribile e crudele, l’unico atto possibile per chi non ha più ideali né dei. Stiano zitti i medici, semmai a chi vuole leggere Drieu consiglino di tenere a portata di mano un flacone di antidepressivi, ma per carità non lo si liquidi con l’etichetta del depresso.

L’opera di Drieu è una scomoda riflessione sul togliersi la vita. E tutto ciò con il senno di poi sembra rispecchiare la crisi autolesionistica che attraversa l’Occidente. Il bello è che lui credeva nell’immortalità dell’anima, anche se in senso più induista che cristiano. Accanto al suo cadavere fu trovata una copia delle Upanishad. Drieu aveva cercato, affacciandosi alla filosofia, al cristianesimo, infine alle tradizioni dell’estremo oriente, senza trovare una via d’uscita. La sua letteratura dice questa ricerca. Dalle Memorie di Dirk Raspe, in cui racconta Vincent Van Gogh, grande suicida, a Fuoco Fatuo, in cui la morte dello scrittore surrealista Jacques Rigaut, suo sodale, è il presupposto per scrivere di getto i pensieri di un uomo incapace di appartenere alla realtà e di amare perché “non può toccare niente” e soltanto la pistola è finalmente reale, un oggetto solido attraverso cui realizzare finalmente qualcosa di tangibile. Ed eccolo, terribile e crudele, l’unico atto possibile per chi non ha più ideali né dei. Stiano zitti i medici, semmai a chi vuole leggere Drieu consiglino di tenere a portata di mano un flacone di antidepressivi, ma per carità non lo si liquidi con l’etichetta del depresso.

C'est à la date du 9 janvier 1900 que Léon Bloy recopie dans son Journal Le Siècle des Charognes, paru le 4 février de la même année dans le cinquième, et dernier, numéro de Par le scandale. Le texte est dédié à «quelqu'un» sur lequel Bloy ne souffle mot, puisqu'il a dû cesser à cette date d'être l'ami du mendiant ingrat, en fait un certain Édouard Bernaert, poète belge qui fut ami de Léon Bloy, et créateur de l'éphémère revue en question.

C'est à la date du 9 janvier 1900 que Léon Bloy recopie dans son Journal Le Siècle des Charognes, paru le 4 février de la même année dans le cinquième, et dernier, numéro de Par le scandale. Le texte est dédié à «quelqu'un» sur lequel Bloy ne souffle mot, puisqu'il a dû cesser à cette date d'être l'ami du mendiant ingrat, en fait un certain Édouard Bernaert, poète belge qui fut ami de Léon Bloy, et créateur de l'éphémère revue en question. Comme il serait réjouissant, tout de même, qu'un moderne contempteur de baudruches pieuses, crevant de honte à l'idée que, lui-même catholique et pourtant «forcé d'obéir au même pasteur» (p. 18) que les ouailles dégoulinantes de mansuétude, devrait bien finir par reconnaître que les catholiques français, ces cochons, sont bel et bien ses frères ou, du moins, précise immédiatement Léon Bloy, ses «cousins germains» (p. 17), comme il serait drôle et intéressant qu'un tel butor évangélique ose affirmer que les ouvrages publicitaires de Fabrice Hadjadj ne sont rien de plus qu'une amélioration toute superficielle du catéchisme délavé qu'il a pieusement écouté (d'une seule oreille) lorsqu'il était petit, ou bien que

Comme il serait réjouissant, tout de même, qu'un moderne contempteur de baudruches pieuses, crevant de honte à l'idée que, lui-même catholique et pourtant «forcé d'obéir au même pasteur» (p. 18) que les ouailles dégoulinantes de mansuétude, devrait bien finir par reconnaître que les catholiques français, ces cochons, sont bel et bien ses frères ou, du moins, précise immédiatement Léon Bloy, ses «cousins germains» (p. 17), comme il serait drôle et intéressant qu'un tel butor évangélique ose affirmer que les ouvrages publicitaires de Fabrice Hadjadj ne sont rien de plus qu'une amélioration toute superficielle du catéchisme délavé qu'il a pieusement écouté (d'une seule oreille) lorsqu'il était petit, ou bien que

Richard Millet est classé à l'extrême-droite par ceux qui ne l'ont pas lu et se permettent de le juger. C'est le

Richard Millet est classé à l'extrême-droite par ceux qui ne l'ont pas lu et se permettent de le juger. C'est le